Collecting is Storytelling

An overview of the history of comic books, through the eye of a collector.For as long as I can remember, I've been obsessed with collecting things. From coins and stamps, to random tchotchkes and found objects, assembling diverse artifacts that share certain traits or contexts has always amused me. As a kid in the 90s, I was awe-struck by anything related to Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, Spawn, and Pokémon. Today, I’m a full-blown “adult” fascinated by pre-code horror and Silver age Batman, to name a few.

A glimpse into my office, which I lovingly refer to as “the comic shop”. This photo was taken in May of 2023. It already looks different.

Collecting is storytelling. The collective mass of stuff that accumulates in the process of moving through life tells us a story about the history of our society and selves. When we accept the license to go down a rabbit hole, and bring some thing back with us, we make tangible the obsessions, curiosities, and fantasies that make our mind race.

Collecting Comic Book History is a growing personal archive of key comic books and classic covers that collectively depict an oral history of comics, from the vantage point of a die-hard collector. Each section (below) focuses on a different historical moment through a brief written introduction, and a selection of books from my own collection that serve as illustrations for the topics discussed. It is my intention to update this page as my collection grows and morphs.

Last updated: March, 2025The Platinum Age

The First Comic Book (?)

What was the first comic book? Unfortunately, it depends on who you ask, and how they define "comic book". Some turn to Outcault's influential newspaper strip, "The Yellow Kid"; Töpffer's "The Adventures of Mr. Obadiah Oldbuck", a sequential art piece published in a newspaper supplement in 1842; ancient cave paintings; Eadweard Muybridge's seminal piece, "The Horse in Motion".

My own definition of "comic book" is a narrative, or series of narratives, that leverage the unique affordances of sequential art in the context of a smaller book, typically 32 pages, intended for sale or distribution to an audience on an ongoing-basis or as a one-off/standalone piece. This definition implies a perspective that none of the aforementioned examples qualify as "the first comic book".

The first true "comic book", by my definition, is Famous Funnies #1. This comic strip anthology was the first book of its kind to hit the newsstands, paving the way for countless predecessors. While the book did not include any original material (the content reprinted popular comic strips of the day), the format and means of distribution was groundbreaking. Prior to the scaled model pioneered by Famous Funnies #1 that is still used to this day, comics as we know them were distributed only as inserts in a newspaper, collected in a traditional paperback or hardcover book; given away as part of a corporate marketing scheme or social/public sector advocacy campaign. If comics are fundamentally about bringing a story to life through sequential art; packaging and presenting the content as a stand-alone publication or ongoing series, and assigning value to said content, nothing compares to the impact of Famous Funnies #1.

My copy of Famous Funnies #1 is a CGC 6.0 with off-white to white pages. The book is restored (B-3). Restoration does not include trimming. This particular copy comes from the collection of Jon Berk, a celebrated comic book collector and historian. I owned this book for about a year before selling it for a key Batman book from the Golden Age (we’ll get to that!).

To fully understand the so-called "Platinum Age" of comics, one must have a grasp for the social, political, and economic realities of the day. The Platinum Age of comics has been identified as commencing in 1897, with the debut of newspaper strips like the "Yellow Kid", and concluded the moment Action Comics #1 (the first appearance of Superman) hit the newsstand in 1938.

Between 1897 and 1938, the United States underwent significant social, cultural, economic, and political changes. This period saw the emergence of industrialization, urbanization, and modernization, which led to the growth of cities, increased production, and greater wealth for some Americans. However, it was also a time of social and economic inequality, with many working-class Americans facing poor living and working conditions. The period was marked by significant political and social movements, including the women's suffrage movement, the labor movement, and the civil rights movement. The country also faced major challenges, such as World War I and the Great Depression, which had a significant impact on the economy and society. Overall, this period was characterized by rapid change, social and economic upheaval, and significant progress towards greater equality and social justice.

This time of rapid growth, combined with a climate that was entirely overwhelmed by a series of unique and existential challenges, is a natural breeding ground for new forms of communication, expression, and self-soothing. In a time of great change and stress, it makes sense that the demand for comic relief in a format that was affordable to the average Joe would come to be.

The Golden Age

When America Needed a Hero…

In 1938, the comic book industry as we know it was born with the release of Action Comics #1. Not only did this comic contain the first appearance of Superman, it is widely recognized as the first superhero comic. And it was only 10 cents. Superheroes that debuted at the start of the Golden Age went on to have a profound impact on our culture. These heroes included: Wonder-woman, Superman, the Flash, Captain America, Mr. Marvel, and Batman (my personal favorite).

During WW2, the entire world was at edge. People longed for a special kind of hero that could make everything better. Superman and Captain America embodied the patriotic values that dominated society at the time; Batman made it clear that anyone could be a hero (well, as long as you can afford it).

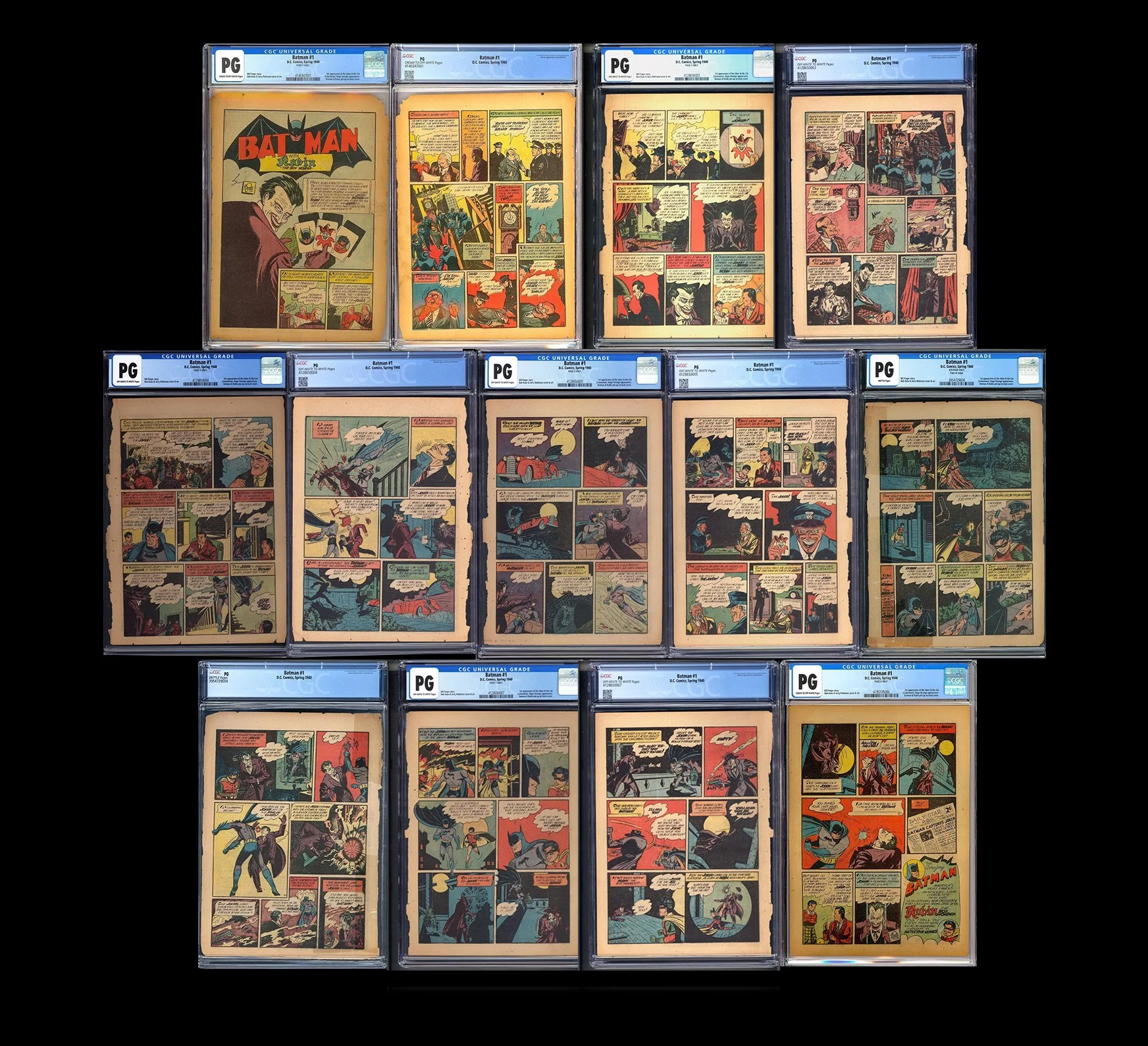

My dream is to own a copy of Detective Comics 27, the first appearance of Batman. But before I can get that book, I need to get a copy of Batman 1. Unfortunately, Batman 1 is incredibly expensive. So, for a while, I collected individual, authenticated, pages from the book. Think of it like a comic book collecting version of Johnny Cash’s hit, “One Piece at a Time”. I recently sold this page at auction.

At one point, I owned pages 2-8 of Batman 1, which includes Joker’s first appearance, along with the entirety of his first story.

Batman has the most intriguing origin story of any superhero in my mind. Not only is it a story that can be told within a single sentence, there is a lot of deep undertones in its meaning and in the consequences of that very story. First, the Batman goes out at night to fight the crime that the systems he has benefited from his whole life have ultimately played a role in. It’s a harrowing tale of capitalism, as well as the ugly face that the mask of philanthropic efforts can often cover.

Second, it tells a deep story of the impact trauma can have on someone’s life. As a child, Bruce Wayne’s parents were murdered before his eyes. He would go on to grow up and build a secret life centered around avenging their murder. However, Batman has only ever been able to face those fears in costume. One could argue the moment Bruce Wayne can lose his costume is the moment he actually achieves a sense of peace.

Third, the notion of a secret identity is one we see often in superhero comics, has long intrigued me, and is of course core to the story of Batman. The idea that we are fluid beings who can often appear differently in different contexts, and at times can lose sense of who we truly are is profound and relatable.

Popular Comics 101 in a CGC 9.4. This book is an excellent example of blatant advertising and influence of government in the comics

Superhero comics quickly morphed from a more abstract and symbolic take on heroism to a very direct, politically-charged narrative. In fact, the US government partnered with a group know as the War Writer's Board to create comics that paint a powerful and positive picture of its military forces, and life in America at-large. This strategy to influence Americans was brought to life through anti-Japanese covers; images depicting Nazis as a defeat-able enemy; obvious propaganda to promote civic engagement and support, including advertisements for war bonds and other "patriotic" acts.

By the end of the war, comic book readers longed for a fresh narrative. Now less fixated on finding a hero, comic book readers were ready to put a name to their day-to-day fears and anxieties, while exploring genres that resonated with their feelings and emotions.

…Until We Didn’t.

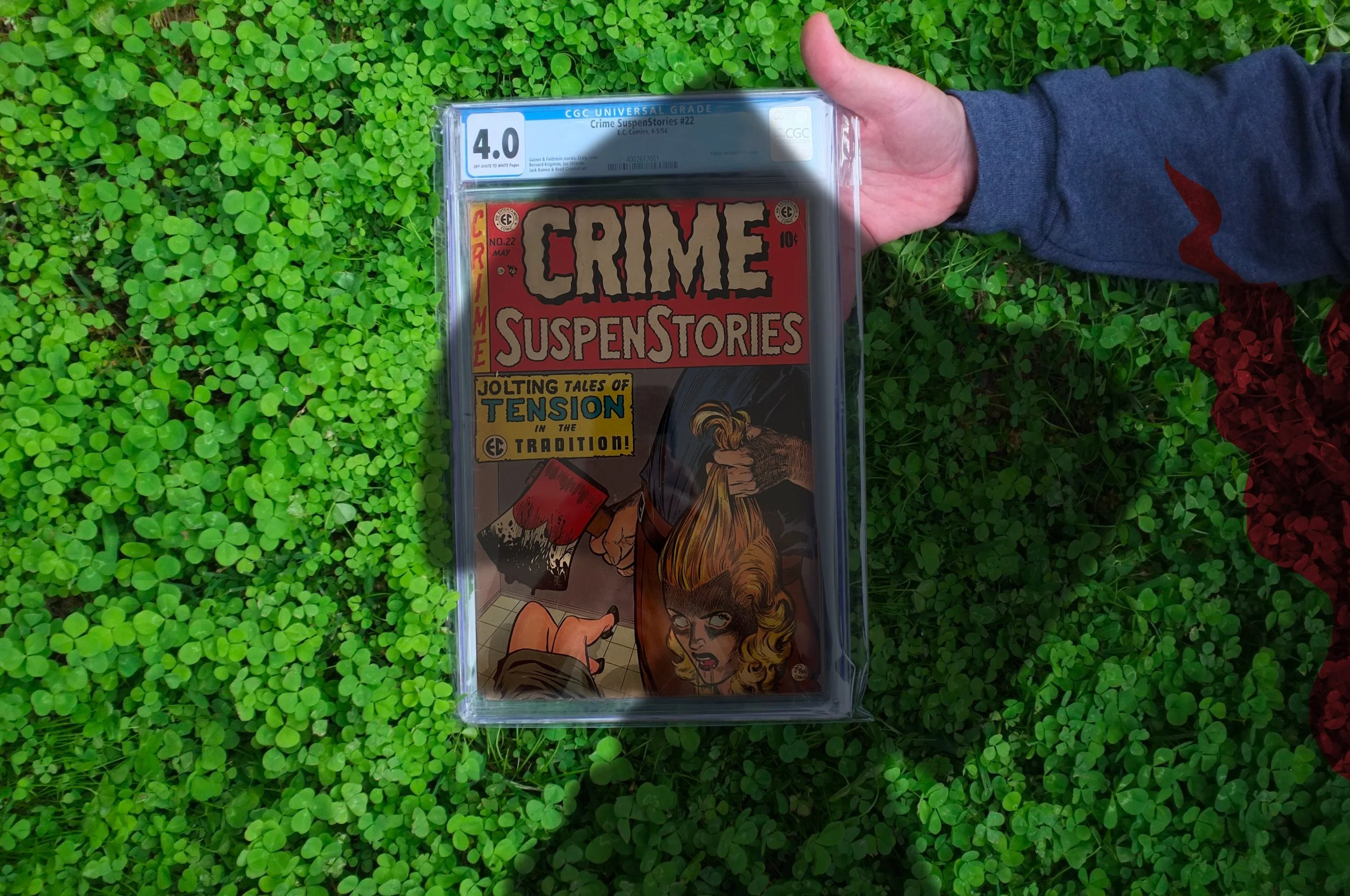

It's the early 1950s, and the comic book industry was booming. New horror, crime, and romance titles were raking in the dough. One publisher in particular, EC Comics, had a bullpen that was stacked with the best talent in both storytelling and illustration: Wally Wood, Johnny Craig, and Ray Bradbury, to name a few. This desire for new content that would elevate comics to a form of serious literature inspired experimentation, and a desire to push and test limits. The result? Extreme violence; risqué subject matter; nightmare-inducing narratives; and, best of all, incredible cover art.

I have 130 original EC Comics in my collection. I am actively working toward obtaining complete runs of key EC titles. Of course Crime Suspenstories 22 is one of my top five covers from the collection as a whole, and I am working toward owning as many copies as possible.

There are a number of visual tropes that hit especially hard when browsing the work produced in this era, each of which are highly saught-after by the more niche and refined collector, including: bondage and torture covers, skull covers, "Good Girl Art" covers (or, the classic "damsel in distress", covers featuring Satan/the Devil, "Bad Girl Art" covers (AKA "femme fatal"), sexually explicit "headlight" covers (artwork that emphasizes the female chest), 3-D covers, and more.

A few former books from my personal collection that represent well, the common tropes of the time. It is worth noting the Phantom Lady book comes from the Promise Collection. Here’s what Heritage Auctions has to say about this fascinating pedigree: “In the early 1950s, a young man called Robert was drafted by the Army to fight in Korea. His younger brother, known as Junie, enlisted in the hopes of keeping watch over Robert. Junie had but one request of his big brother – that Robert take care of his collection of funny books should anything happen to him in battle. Robert knew how dear those books were to his brother. So he promised him: Yes, of course. He would take care of those funny books. If something happened. God forbid. Then Junie was killed in action. He was 21 years old.”

Captain America, a key superhero in American culture, like all superheros at the time, tanked in popularity. As an attempt to draw more attention to the character and align with trends, Captain America was re-imagined to follow a horror format for just two issues before pulling the plug and exploring more authentic ways to modernize.

This era is known as the Golden Age because it was the last hurrah for creative naivaté; a time before constraint, where artists and writers were truly free to explore the limits of their creative vision. But all good things must come to an end.

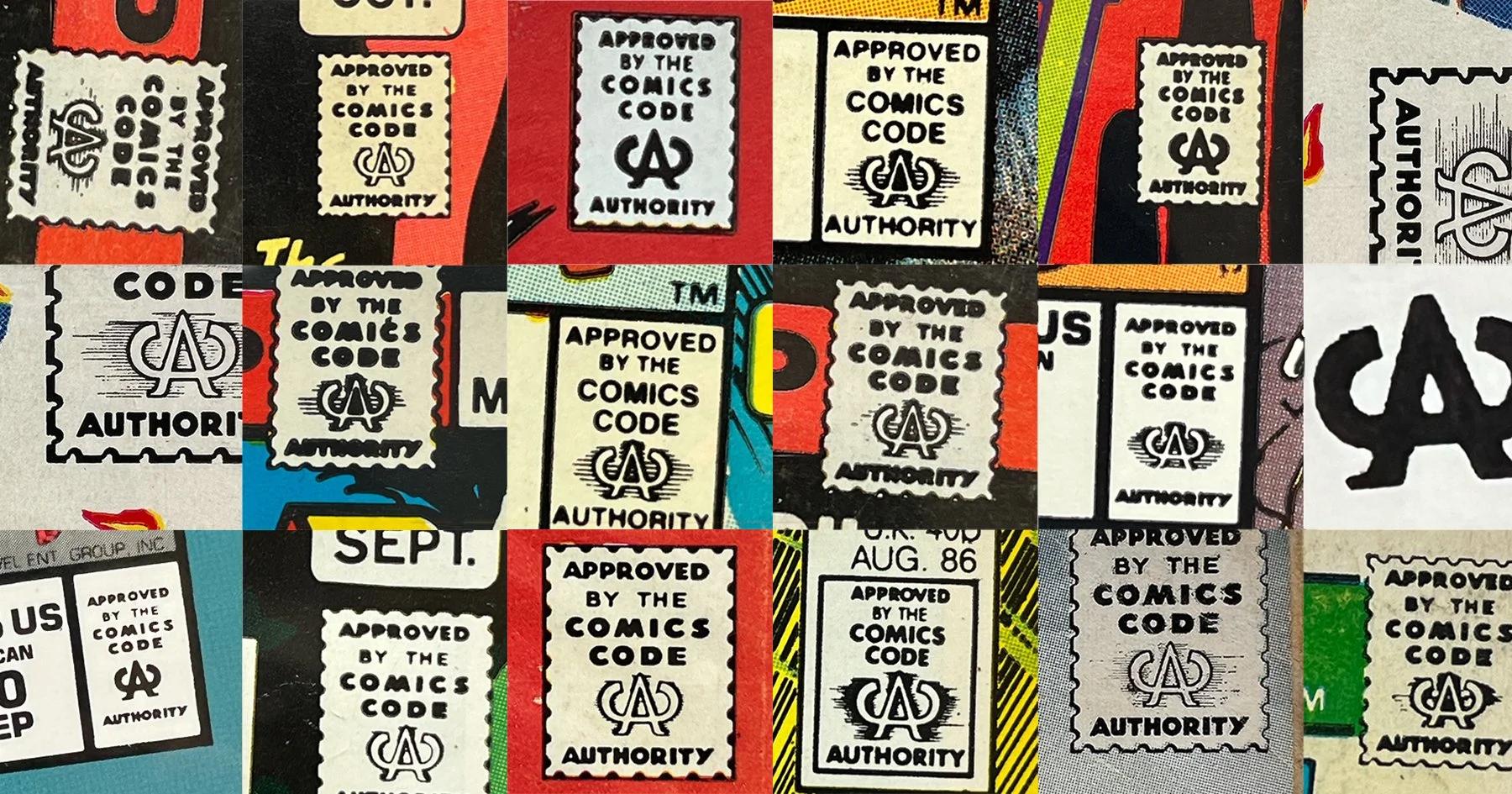

In the 1950s, there was a widespread anti-comics crusade in the United States, spearheaded by psychiatrist Frederic Wertham and supported by various parent groups and religious organizations that even hosted public book burnings. Wertham, the original "Karen", argued that comics were corrupting youth and causing juvenile delinquency. His infamous book, Seduction of the Innocent, cites examples of violent and sexually explicit content in comic books as not only be influential, but instructional. This led to a Senate Subcommittee on Juvenile Delinquency hearing in 1954, where Wertham testified against comics. In response, the comic book industry created the Comics Code Authority, which imposed strict guidelines on comic content, including prohibiting depictions of violence, drug use, and sex. This is not dissimilar to the systems put in place for film, music, and video games; the challenges faced by San Francisco's City Light Books upon publishing Howl, but Allen Ginsberg; the current debate around stand-up comedy. Today, we see Nadya Tolokonnikova, of Pussy Riot fame, as a prime example of pushing the limits of what we might expect from the intersection of the arts and activism. Her most recent work, “Putin’s Ashes”, is an anti-Putin performance and conceptual art installation that landed the artist on Russia’s Most Wanted List.

I'm deeply inspired and motivated by artistic pursuits that find, test, and break through these kinds of limits while fundamentally challenging us through the images and acts we see; the music and thought leadership we hear; the physical and digital media we read. Prior to the Comics Code Authority, this "Golden Age" of comics was the perfect moment to test those limits.

My copies of Seduction of the Innocent and Parent’s Weekly Magazine, two early publications that were central to the anti-comics movement, and eventual shift in comics that took the medium away from the more “serious” or realistic topics and scenarios almost overnight.

The Silver Age

Here Comes the Code

As the horror, romance, and crime titles of the 1940s and 50s were seeing unprecedented success, a small but mighty group of people were calling for more wholesome content. When the Comics Code Authority was first established in 1954, publishers faced specific constraints on the content of their comic books. These included bans on depictions of violence, horror, sex, and drug use. The code also mandated that "good" must always triumph over "evil" and prohibited the portrayal of any sympathetic or romantic relationships outside of marriage. Publishers that wanted to “go with the code” would submit their comics for approval by the Comics Code Authority before they could be distributed, which resulted in self-censorship and a significant reduction in the variety and creativity of mainstream comic book content.

Collage of Comics Code Authority seals on books in my current or former personal collection.

The code had a lasting impact on the industry, and even after it was loosened in the 1970s, its effects on the comics medium were felt for decades. To give you a sense of the language of the code, I’ve included 10 of my favorite lines:

“Policemen, judges, Government officials and respected institutions shall never be presented in such a way as to create disrespect for established authority.”

“No unique or unusual methods of concealing weapons shall be shown.”

“The letters of the word “crime” on a comics-magazine cover shall never be appreciably greater in dimension than the other words contained in the title. The word “crime” shall never appear alone on a cover.”

“No comic magazine shall use the word horror or terror in its title.”

“All scenes of horror, excessive bloodshed, gory or gruesome crimes, depravity, lust, sadism, masochism shall not be permitted.”

“Scenes dealing with, or instruments associated with walking dead, torture, vampires and vampirism, ghouls, cannibalism, and werewolfism are prohibited."

“Nudity in any form is prohibited, as is indecent or undue exposure.”

Females shall be drawn realistically without exaggeration of any physical qualities. NOTE.—It should be recognized that all prohibitions dealing with costume, dialog, or artwork applies as specifically to the cover of a comic magazine as they do to the contents."

“Passion or romantic interest shall never be treated in such a way as to stimulate the lower and baser emotions.”

“Sex perversion or any inference to same is strictly forbidden."

While I find the above highly entertaining, this particular line is my favorite: “No comics shall explicitly present the unique details and methods of a crime.” The medium of comics lends itself so well to the production of instructional sequences, that the Supreme Court believed its influence needed to be contained. In doing so, the educational and informative potential of comics is validated; comics are proven as powerful tools for educators. More on that later.

While comics could be published without the Code's stamp of approval, fear of prosecution in the early days of the code drove retailers toward extreme measures to comply. Books that arrived in store without a Comics Code Authority seal were often returned. Take EC Comics for example: publisher William Gaines chose not to comply when releasing his latest title, MD, an anthology of comics related to medical conditions and the day-to-day of doctors, so the first issue was released without going through the proper channels of review. When many of the books came back to Gaines, he knew it was time to give in, or get out.

My run of MD.

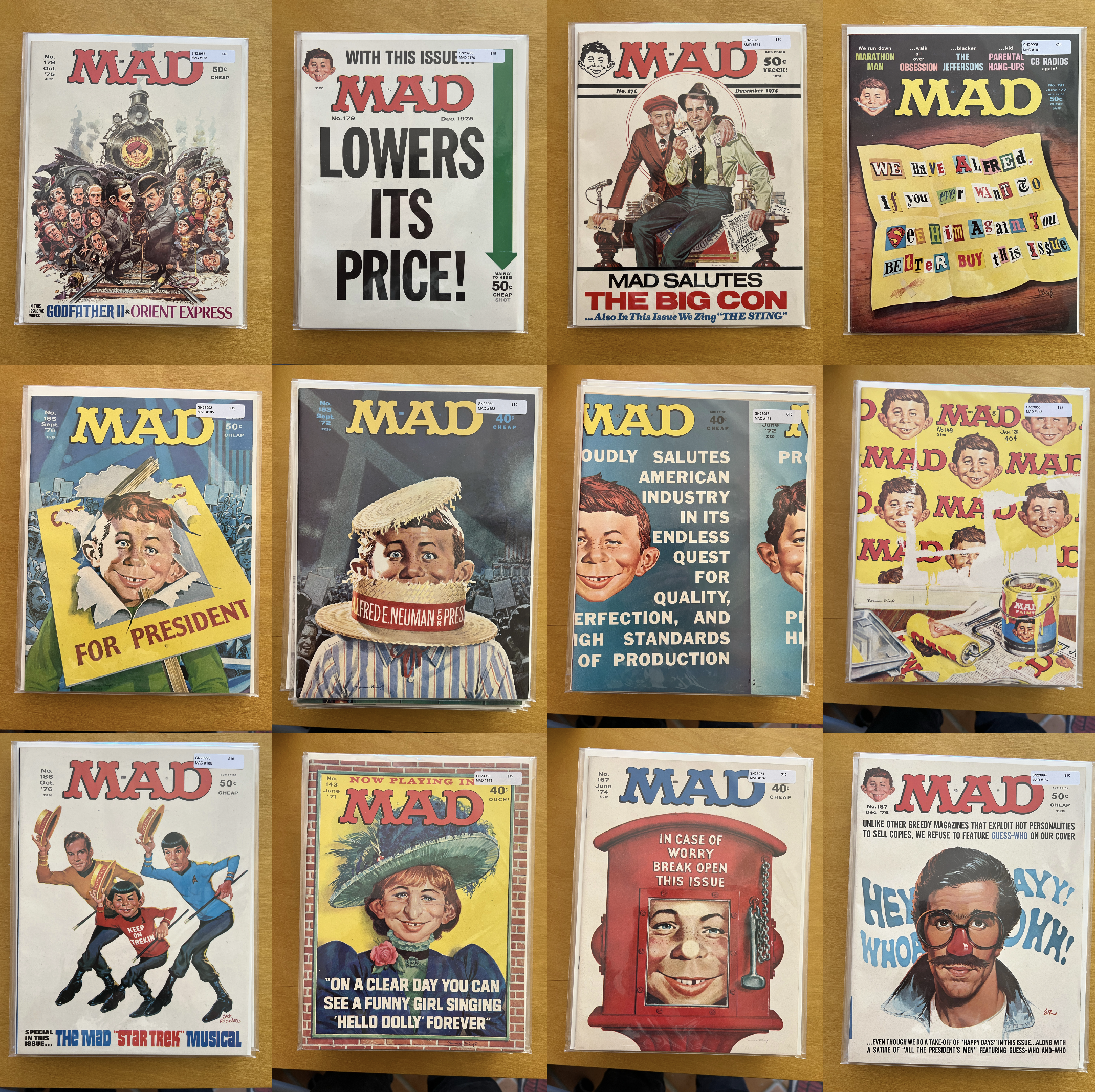

But the Code's severe limitations on essentially everything EC specialized in resulted in narratives that pailed in comparison to the publisher's pre-code masterpieces. Soon, EC Comics would put an end all of its titles, except for one that we've all heard of: MAD Magazine.

After 24 issues as a standard comic, Al Feldstein, the editor of MAD, got to realize his fascination with the magazine format. He felt the format brought a different kind of prestige, and allowed more room to advance narratives. Luckily, retailers were also less discerning when it came to magazines, as there was no expectation of the format requiring Comics Code Authority review.

For the comics that did survive, a new "Silver Age" of comics was on the horizon; an era in which comics became more fantastical and all-around wacky.

I do enjoy casually collecting MAD Magazine as well. Here are 12 brilliant covers from the 70s that I picked up at Stuart Ng’s in Torrance.

Comics for Other Things

Earlier, I cited “no comics shall explicitly present the unique details and methods of a crime” from the Comics Code as validation of the educational potential of comics. I’m interested in comics about topics outside of what you’d expect from the medium. I’m also interested in comics that explored different formats/sizes (like promotional comics and ashcans).

Two of the best educational comics I’ve had in my collection, including the first appearance of Smokey the Bear and a comic to inspire people to use seatbelts: “It’s fun to stay alive”.

I’m also interested in the choice to leverage the medium of comics for adaptations of movies, cartoons, TV shows, and other narrative media. The sequential art format is a great tool for representing time-based media in an accessible nature. This has long been a strategy in the film industry. A great example of this are the comic book adaptations of Scooby Doo, the Flintstones, and the Jetsons.

While adapting animated material to the medium of comics is quite natural, comics adapting movies and television had a tendency to rely upon photo covers, or photo-realistic paintings. An excellent example of this is Howdy Doody 1, the first TV comic; Strange Adventures 1, which leverages a hybrid photo/drawn cover approach and adapts the seminal sci-fi film, “Destination Moon”.

My favorite TV/Movie adaptations that I’ve previously owned.

Comics were so popular, people wanted them in different shapes and sizes! In the late 1940s, Cheerios started releasing free mini comics in their cereal boxes. Most, if not all, of these giveaways featured Disney characters. The rarest, and most controversial of the Cheerios Giveaways is Donald Duck's Atom Bomb (#Y1 1947). Due to the atomic bomb themes and imagery within this mini comic, Disney will never reprint the material.

My former copy of Donald Duck’s Atom Bomb. An incredible CGC 9.8, with White Pages!

Post-Code

Depending on who you ask, what’s known as the Silver Age of comics began in 1954, 1956, or 1961. Marvel fans claim 1961, as this was the year Fantastic Four Number 1 was released, and would change the course of Marvel Comics forever. The general majority, however, will argue that the silver age began with the publication of DC Comics' Showcase #4 in October of 1956, which introduced readers to the modern version of the Flash. All debates aside, the Silver age brought us masterpieces that would go on to change the game for comics as a cultural influencer. One of those key books is Amazing Fantasy 15, the first appearance of Spider-Man.

For me, the silver age begins in 1954, after the establishment of the comics code authority shook up the industry as a whole. In an attempt to meet the requirements of the code, many comics went in pretty strange directions with their villains and storylines. The thought was, let’s get this as far away from the sensitive and real life crime, suspense, and horror topics as possible so as to not ruffle any feathers.

The result of this self-censorship movement is some of the most bizarre and out-of-this-world covers in history. For me, the stand-out above all other titles of the era is Post-Code 10 and 12 cent Batman and Detective Comics. Conveniently, Batman, Catwoman, Joker, Riddler, Penguin, Mr. Freeze, and more… have been some of my absolute favorite characters since I was a kid!

My favorite Silver Age Batman and Detective Comics covers from my personal collection. I’m particularly proud of the Detective Comics 241. Believe it or not, 8.5 is the highest grade for this sought cover. Also, the Batman 164 comes from the Fantast Collection, which has a powerful backstory. Learn more at https://www.sellingsuperman.com/.

Around the World

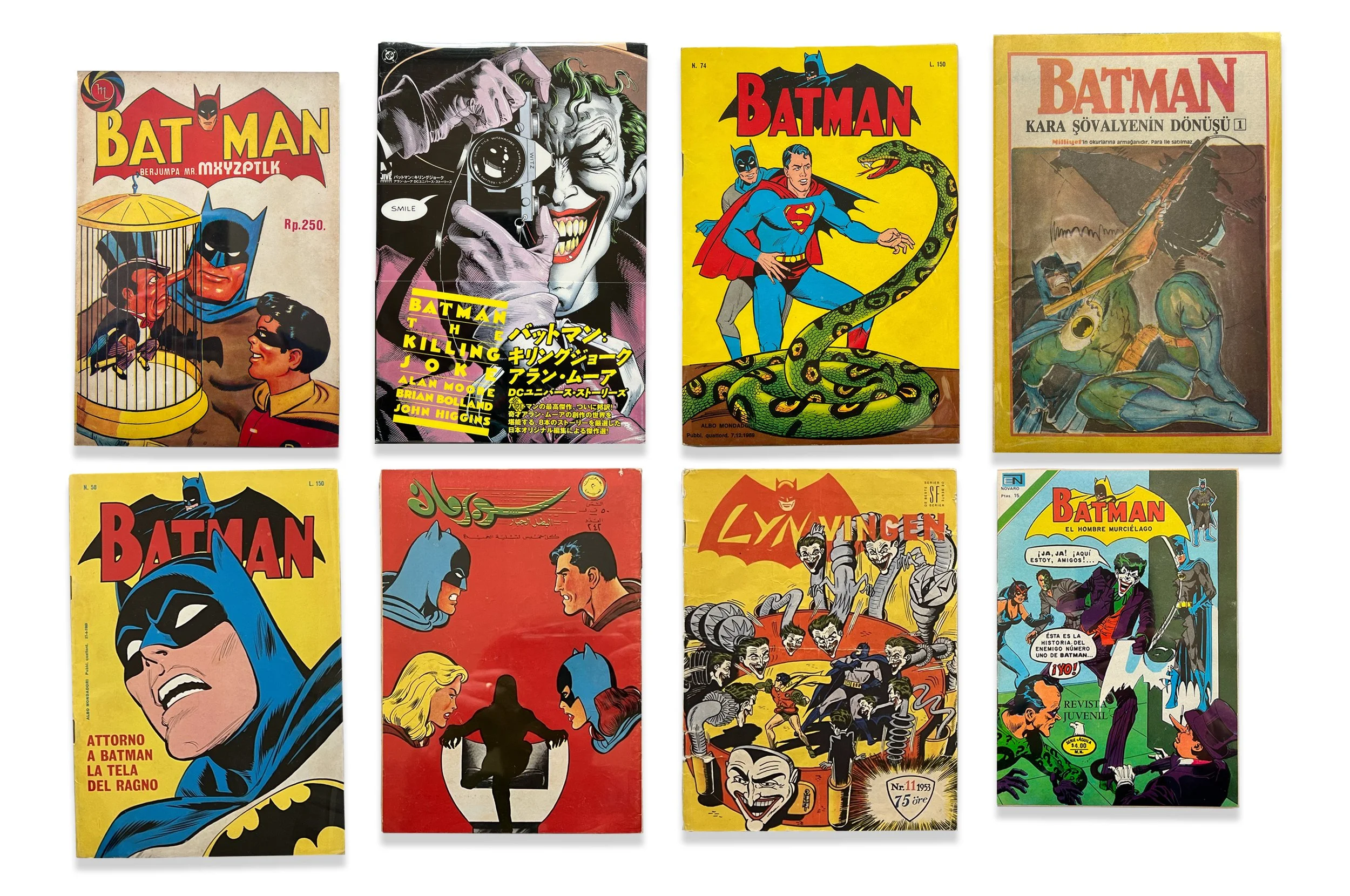

Aside from American History and Comics, I’m fascinated by the impact these classic characters have had on cultures and communities around the world. While open to broadening the scope of my international comics collection, I currently have a focus on Batman (with one exception). Here are a few of my favorites from the collection:

These books span the gold, silver, and bronze ages of comics. So far, I have been able to include Indonesia, Japan, Italy, Turkey, Lebanon, Norway, and Spain.

While I do focus on international Batman titles, I couldn’t pass up the opportunity to own the first Japanese printing of Amazing Fantasy 15 (Spider-man’s first appearance)!

Meanwhile, in San Francisco…

Outside of the mainstream, there was an entirely different world of comics brewing. Underground Comix was solidified as a key movement and shift in comic book history with the release of Crumb’s seminal ZAP Comix. Incredibly crude, the underground movement’s role in shaping comic books as we know them today can be seen as the next evolution of EC Comics’ limit-pushing tendency.

It was in the pages of underground books that some of the most out there and outlandish artwork could be found. The underground movement also resulted in books that would really push boundaries: the first autobiographical comic, the first all-female written and produced comic book, a book that saved the dolphins, and so much more.

A selection of my favorite underground comics from my personal collection. Each of these, I personally submitted to CGC. I won them in an auction, and many of these copies were from the collection of publisher Ron Turner. Fun fact: I submitted a comic that I wrote and illustrated to Ron Turner in the middle of COVID, and this was his reply: “Sorry about your bird shit dream. The olden word for manure was Mano or Manos, because manure was spread by hand and I think there was a hand gesture that meant kind of like "same old shit" when asked how you were. And, the most sought after fertilizer was guano, so there might be a deeper connection. Bat shit is the highest prized guano, but it is a flying mammal, not related to the flying dinosaurs we eat at the Cornel's fry factory.” Truly one of the best rejection emails I have ever received.

The Bronze & Modern Age

Stuff Gets Real

A defining feature of comic books written with the Code on the mind was the departure from real world problems and struggles. As we moved from the 1960s to the 1970s, the desire to tackle these taboo topics comes to a tipping point. Green Lantern 85 not only has one of the most powerful and iconic covers in all of the Bronze Age, the story inside is pioneering in its exploration of drug addiction. Amazing Spider-Man 121 includes the death of Gwen Stacy. When Gwen’s neck snapped mid-rescue attempt from Spider-Man, readers were left stunned. Batman 251 for its iconic cover art by Neal Adams; for serving as a pivotal turning point in the Joker’s revitalization as a homicidal villain. Iron Man 128 for its classic alcohol abuse cover. Amazing Spider-Man 96 for the bold decision made by Stan Lee to publish without the approval of the Code. Stan believed the book’s underlying anti-drug message was too important to hold back.

My wife got me this book for my 34th birthday, along with a bottle of scotch that she custom-designed to match the cover! Such a treasure! This cover is an absolute classic from the Bronze Age and has been subject to many homages. Speaking of birthdays…

The Eighties

I was born in September, 1988. When I found out some collectors like to hunt for their “birthday book”; books that were published the month and year of their birth, I was inspired.

My collection of “birthday books”; books published the month and year I was born (September, 1988).

After browsing dozens of covers from all kinds of publishers, I was pleasantly surprised by how many significant comics were published in September, 1998. AKIRA 1, the ground breaking manga’s debut in English. V for Vendetta 1, the start of a story that would go on to be adapted as an iconic film. Joe Fixit’s first appearance in Incredible Hulk 347. But my personal favorite cover art from the month?

Batman 423.

My first copy of Batman 423 was a CGC 9.4. It was the first CGC graded book I ever purchased, and I bought it as a birthday gift to myself. Eventually, I sold the book, and put the money toward a nice looking raw copy and some other books. In buying the raw copy, I had the intention of it becoming the first book that I personally submitted to CGC. The dealer told me it was a 9.0 (VF/NM), and in looking at it closely, I agreed with him. Unfortunately, CGC didn’t agree. It came back a 7.0! I was so frustrated that I sold that copy, along with several other items from my collection, and eventually bought a CGC 9.6. I was happy with the copy, but when browsing eBay, I noticed a 9.8 was available at a price well below the average recent sales. I “watched” it, for the heck of it, and to my surprise, the seller sent me an offer for an even LOWER price. At that point, I had to do it. I sold my 9.6 copy on Whatnot, and cobbled together the rest of the funds to make it happen.

You’ll learn quickly by browsing my collection that I like the Joker and anything Batman-related. The best Joker story of all time is Batman: The Killing Joke. While Frank Miller’s Dark Knight Returns is credited for moving comics into darker undertones, the Killing Joke is a stand-out for its graphic narrative.

At one point, I had the first through ninth printings of Batman: The Killing Joke in a CGC 9.6 or better.

Alternative Comics

The rise of independent publishing after the underground movement, but before webcomics, paved the way for an even deeper reflection on the role and limits of comics. One prominent example of alternative comics is "Love and Rockets," created by Gilbert and Jaime Hernandez. The series debuted in 1981 and gained popularity for its unique genre-bending narratives and incredible artwork. Quickly picked up by the groundbreaking publisher, Fantagraphics, "Love and Rockets" helped establish the alternative comics movement by challenging the dominant superhero-centric narrative of mainstream comics.

My copy of Love & Rockets 1. I’d love to upgrade one day, or get my hands on a pre-Fantagraphics copy. Those are hard to find because they were just xeroxed at a local print shop somewhere in California.

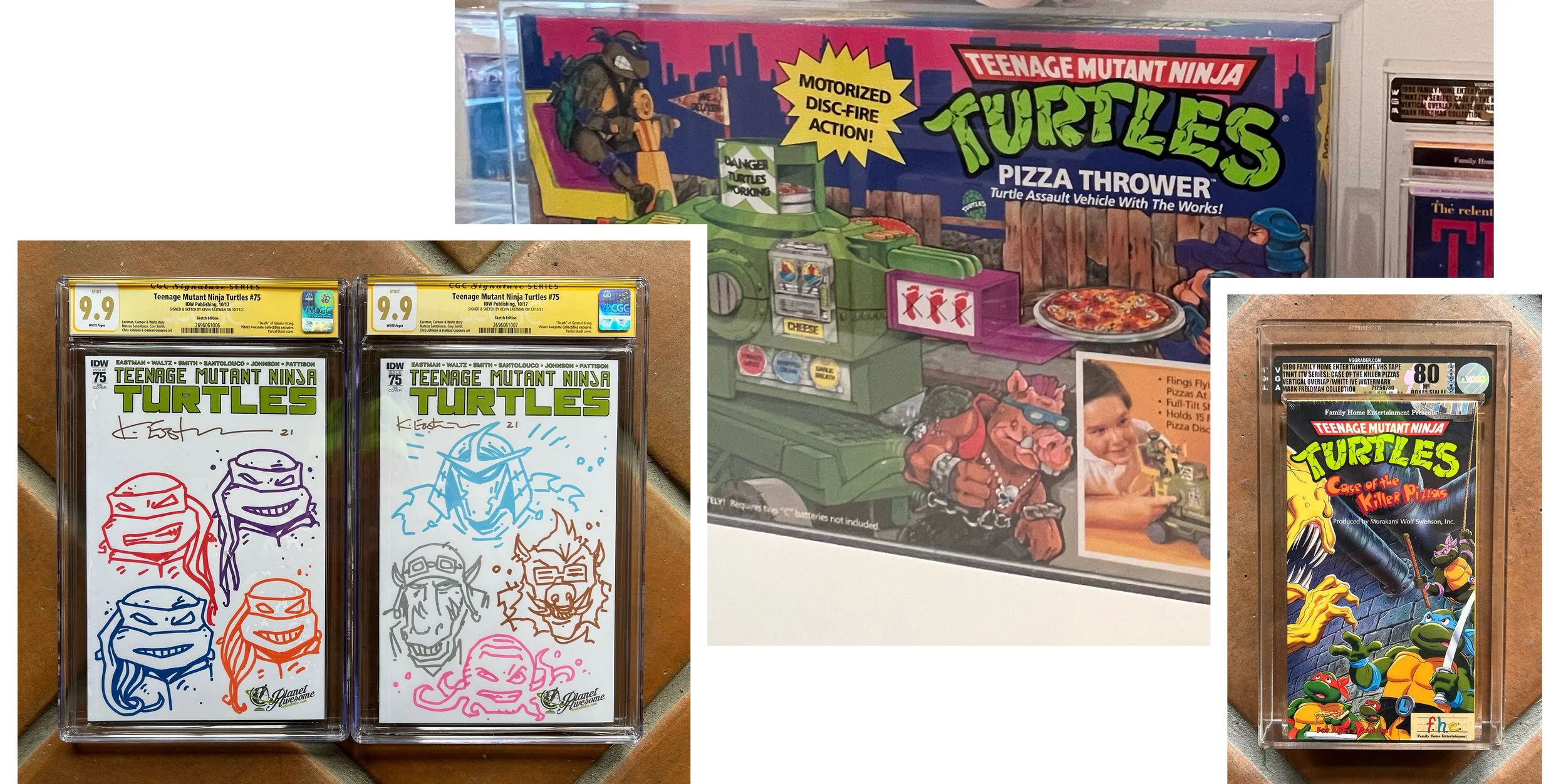

Perhaps the most well-known example of independent publishing is the "Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles" (TMNT), created by Kevin Eastman and Peter Laird in 1984. Initially conceived as a parody, TMNT rapidly great to become the successful independent comic book series, breaking the mold with its unconventional concept and humorous storytelling. The success of TMNT demonstrated that alternative comics could resonate with a wide audience beyond traditional superhero fare.

Here are some of my favorite TMNT items. A pizza thrower, a graded VHS, and two CGC 9.9 comics with original art by creator, Kevin Eastman.

In the 1990s, Image Comics emerged as a significant force in the industry, building on the foundation laid by alternative comics of the previous decade. Image was founded in 1992 by several renowned artists, including Todd McFarlane, who is the creator of a childhood favorite of mine: "Spawn." Spawn, created by McFarlane, showcased a darker and edgier superhero narrative, with supernatural elements and a morally complex protagonist. Spawn is a great example of the distinct style and storytelling approach that Image Comics sought to promote (of course with plenty of rippling muscles).

My Spawn collection, including a commissioned piece by Legal Burning, which recreates the cover of Spawn 1 using a unique paper-burning technique.

Building upon the underground movement, the independent and alternative comics boom and Image Comics successfully subverted what we might expect from a traditional comic book. Alternative comics challenged the dominance of mainstream superheroes and offered fresh perspectives, diverse characters, and experimental storytelling techniques. Image Comics further embraced this spirit by providing a platform for creators to retain creative control and ownership of their work. This shift empowered artists to take risks, explore unconventional themes, and push the boundaries of storytelling.

Spawn, in particular, became a flagship title for Image Comics. Spawn's dark and gritty aesthetic, along with its willingness to explore mature themes, resonated with readers and proved it was possible for alternative comics to capture a substantial market share. This rich history continues to influence and inspire the evolution of the comic book medium to this day.

Reflections & Curiosities

Having consciously collected stuff for over 30 years, I’ve learned to see a collection as a reflection of its owner, and their interests; where they’d hope to go. One thing I would love to collect are classic superhero covers that feature teaching or higher education classroom/campus environments. It would make for a nice combination of my two major passions: comics and education.

Outside of comics and education, I am a massive BBQ snob. As a way to combine my interests of comics and BBQ, I’ve had a tendency to collect comic book covers with either a BBQ grill or BBQ related food (hot dogs, hamburgers, steak, etc.).

My collection of “BBQ Covers”.

For me, comics are incredibly nostalgic. When I think of comics, I can’t help but think about my childhood, which was full of after-school visits to the comic shop with my grandma. My nostalgia is heightened during even the smallest holidays. Another collecting project I’d love to take on is acquiring an incredible cover from the Golden Age, for each month of the year. Once completed, I’d like to partner with my wife on a limited riso-printed calendar that shares the image of each book, along with some historical context and thoughts.

What comic book history will your collection help you write? What rabbit hole will you go down? What thing will you come back with?

Thanks for sticking with me to the end, folks. I look forward to keeping this page up-to-date as I continue to add key books to my collection. Be sure to come back every once in a while to check-in, and don’t forget to follow me on Whatnot, where I’m @matthewmanos.